On May 23, a police officer arrested Robert W. Frese in Exeter, New Hampshire and took him to the station for booking. Frese is no stranger to law enforcement; in the past, he has been convicted of fraud, criminal trespassing, and a hit-and-run. (His vehicle was easy to track because of its notable vanity plate: TRUMP1.) But this latest arrest, Frese learned, had nothing to do with those earlier mishaps. Instead, he had been apprehended for insulting a police officer on the internet.

The facts of the case, laid out by the Seacoast Online and the criminal complaint against Frese, are straightforward. On May 3, Frese wrote a comment on a Seacoast Online article about recently retiring police officer Dan D’Amato. He believed that D’Amato had treated him unfairly and harshly criticized his alleged misconduct. He then tore into Exeter Police Chief William Shupe, declaring that “Chief Shupe covered up for this dirty cop.”

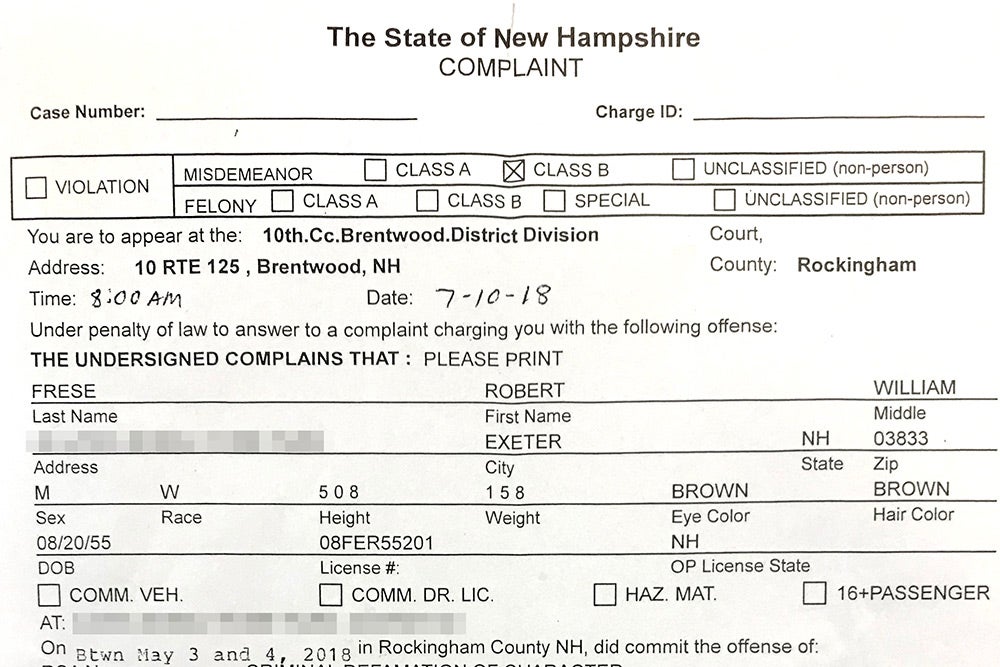

Although the outlet removed the comment, the police charged Frese with criminal defamation of character, a Class B misdemeanor. (In New Hampshire, police departments have authority to prosecute these low-level crimes.) Their complaint allege that he “purposely communicated on a public website, in writing, information which he knows to be false and knows will tend to expose another person to public contempt, by posting that Chief Shupe covered up for a dirty cop.” Frese’s arrest was quite unusual; Class B misdemeanors may result in fines but not jail time, and officers do not typically detain a suspect whose alleged crime may not be punished with a deprivation of liberty. The police released Frese on his own recognizance; his arraignment is scheduled for July 10.

Are these actions by the Exeter police actually legal? Almost certainly not. Political speech—and, in particular, criticism of public officials—lies at the heart of the First Amendment, and the Exeter police would have to overcome several hurdles to secure a conviction. Perhaps most obviously, the law under which Frese was charged may be unconstitutional on its face. The statute criminalizes false speech that “tend[s] to expose” a living person to “public hatred, contempt or ridicule,” without distinguishing between expression directed at private individuals and public figures. But the First Amendment protects some false speech, particularly in the context of political debate. And the astonishing breadth of this law, outlawing any fiction that brings “ridicule” upon a living person, raises serious constitutional concerns.

Even if the statute comports with the constitution, its application in this case remains suspect. Under New York Times v. Sullivan, the government may not penalize criticism of public officials (like a police chief) unless it was made with “actual malice”—knowledge of its falsity, or “reckless disregard” to its truth. That stringent standard protects “rhetorical hyperbole,” which appears to be what Frese engaged in here. It’s not at all clear that Frese intended to express a statement of fact; read in context, his comment seems to imply that the police chief excused the patrolman’s alleged misbehavior. Frese is not necessarily accusing Shupe of a crime so much as drawing an inference from his own (manifold) encounters with the Exeter police. Sullivan plainly protects his right to fling this disparagement at Shupe, even if it might not be true in a strictly literal sense.

Even if Frese did aim to charge Shupe with the crime of covering up police misconduct, Sullivan still likely shields his speech from government sanction. All evidence suggests that Frese believes the Exeter police are engaged in wrongdoing that Shupe has concealed. To successfully prosecute Frese, the police would have to prove that he made his claim knowing full well that Shupe is innocent of this crime, or at least recklessly indifferent to the veracity of his comment. There is virtually no chance that the department could clear this high bar.

Sullivan is particularly relevant here because of the odd facts of this case. It is extremely unusual for the government to prosecute defamation as a crime; the vast majority of defamation claims are civil suits, in which one party seeks redress from the other. Here, the Exeter police are attempting to use the machinery of government to retaliate against an individual for denigrating them. Their charge of criminal defamation is strikingly similar to the old offense of “seditious libel,” or unlawful criticism of the government, which the Sullivan court condemned as anathema to the First Amendment. By using a broad defamation law to suppress speech hostile to state officials, the Exeter police have invoked the spirit of the notorious Sedition Act of 1798, a law the court found to be unconstitutional in Sullivan.

Gilles Bissonnette, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of New Hampshire, is looking into Frese’s case and told me on Friday that he’s disturbed by the prosecution. “It appears that the police may be using this statute to suppress speech that is critical of police,” he told me. “This is deeply troubling.” He added that while there is a “public interest in preventing defamation,” it is “not sufficient to justify the repressive effect that criminal libel prosecutions may have on public expression.”

“It would be prudent,” Bissonnette said, “for the Exeter police to dismiss this charge immediately.”

The situation in Exeter may seem to be little more than a minor mishap. But as pundits and politicians debate censorship on college campuses, it’s important to remember that law enforcement has vast power to suppress expression it dislikes. Immigration activists have credibly accused federal agents of targeting them on the basis of their speech. Demonstrators protesting police brutality have been subject to violence and wrongful arrests because of their expression. Other police departments have allegedly retaliated against citizens who contribute to negative media coverage of officers and journalists conducting investigations. The Exeter case is a bracing reminder that people with guns and badges often present the most immediate threat to the freedom of speech.